Continue reading Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia/Small Lymphocytic Lymphoma (CLL/SLL)

All posts by peferguson

Monoclonal B-Cell Lymphocytosis (MBL)

Monoclonal B-cell lymphocytosis (MBL) was defined by the International Familial CLL consortium in 2005 as a monoclonal B-cell lymphocyte population in the peripheral blood <5,000/uL without evidence of lymphadenopathy (i.e. SLL), an autoimmune/infectious disease or other features diagnostic of a B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder. The 2016 WHO hematopathology revision dropped the requirement of cytopenias or disease related symptoms as adequate to make the diagnosis of CLL.

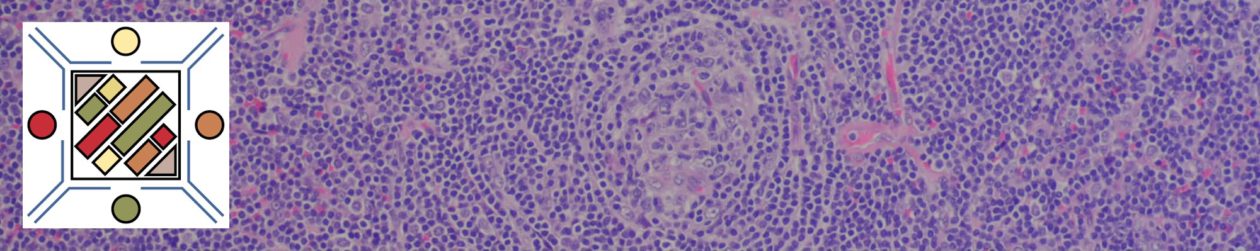

Follicular Lymphoma

Morphology

Immunophenotype

|

Marker

|

Comment

|

|

Negative

|

|

|

Positive

|

|

|

Positive

|

|

|

Positive

|

|

|

Positive (~90%), negative cases do not contain the t(14;18), which is more common in grade 3 cases

|

|

|

Positive, (~88%)

|

|

|

CD35

|

Highlights the follicular dendritic meshwork associated with FL.

|

|

Usually negative, higher grade lesions may be positive

|

|

|

Variable, shows low expression in low-grade processes, in distinct contrast to the high proliferation index and polarity associated with reactive germinal centers.

|

|

|

Negative

|

|

|

|

- Normal reactive germinal centers do not express Bcl-2. In 90% of cases of FL, bcl-2 is expressed, which serves as a diagnostic tissue marker in lymphoma sections.

- CD23 expression by flow cytometry has been associated with lower grade FLs (e.g. grade 1 & 2) and better survival.

Grading

- Grade 1 & 2: <= 15 centroblasts/HPF (based on 0.159 mm² HPF)

- Grade 3: > 15 centroblasts/HPF (based on 0.159 mm² HPF)

- 3A: Centrocytes present in the background

- 3B: NO centrocytes present in the background (not associated with the IgH/BCL-2 rearrangement, and usually lacks expression of CD10 and BCL-2; often MUM-1+)

Pattern

- Predominately follicular: >75% follicular/nodular architecture

- Follicular and diffuse: 25-75% Diffuse areas or follicular/nodular architecture

- Preominately diffuse: <25% follicular/nodular areas (diffuse areas of otherwise grade 3 FL, then that component should be described as a separate component of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma)

Special Subtypes

- Large B-Cell Lymphoma with IRF4 Rearrangement

- Pediatric Follicular Lymphoma

- Occurs in children and young adults with an excellent prognosis, marked male predilection

- The morphology is high-grade (FL grade 3) appearing

- BCL-2 negative, lacK t(14;18)

- CD10 + (usually)

- MUM-1 negative

- Associated with TNFRSF14 deletions of mutations

- Localized process, usually in the head and neck area

- Duodenal Follicular Lymphoma

- Localized lesion

- Grade 1-2 pattern

- CD10/BCL-2 +

- t(14;18) present

- Lacks follicular dendritic meshwork

- Ki-67, low expression

- Excellent prognosis

- Predominately Diffuse Follicular Lymphoma with 1p36 deletion

- Localized mass (often inguinal)

- Diffuse pattern, grade 1/2

- Excellent prognosis

- Immunophenotype: CD20+, CD10+, BCL-2+, BCL-6+, CD23+ (subset of cases)

- t(14;18) NOT present

- 1p36 deletion (not specific)

- Lacks Bcl-2 rearrangement

- Primary Cutaneous Follicular Lymphoma

- In Situ Follicular Neoplasm (ISFN)

References

Lymphomatoid Granulomatosis

Morphology

Immunophenotype

Grading

- Grade 1 – < 5 EBV+ cells/HPF, polymorphic lymphoid infiltrate (large atypical cells rare/absent), No/focal necrosis.

- Grade 2 – 5-20 EBV+ cells/HPF (small clusters of B-cells by CD20), occasional large atypical/transformed cells.

- Grade 3 – > 50 EBV+ cells/HPF, numerous large atypical CD20+ B-cells (may form large aggregates)

References

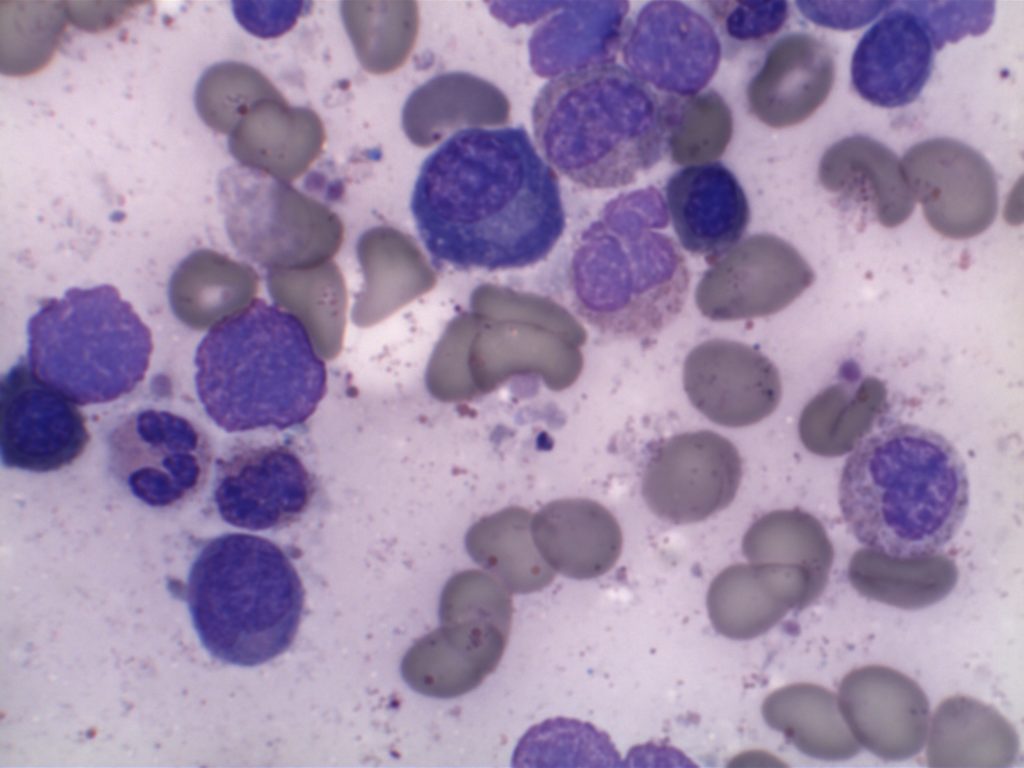

Hairy Cell Leukemia

Morphology

Immunophenotype

- CD19/CD20 +

- CD25/CD103 + (CD25 co-expression with CD103 appears to be specific for HCL relative to the differential diagnosis with HCL-v and SMZL)

- Annexin A1 +

- CD11c +

- TRAP +

- DBA.44 + (thought to be specific for HCL when combined with TRAP +)

- CD5 – (rare cases <5% may be CD5+ by flow cytometry)

- CD10 -/+ (approximately 30% of cases may express CD10 by flow cytomtetry)

- BRAF VE1 (IHC) +

Molecular

- >90% found to have a BRAF V600E mutation. This can be identified by PCR or immunohistochemistry (IHC may be more sensitive than PCR). This appears to be relatively specific (relative to the usual differential diagnosis of HCL) with only rare cases of CLL/SLL, marginal zone lymphoma, and multiple myeloma found to express BRAF V600E IHC stain.

- MAP2K1 mutations (encodes MEK1 downstream of BRAF) in most BRAF negative HCL cases that use IgHV4-34. This mutation finding is not specific to HCL and may be seen in hairy cell variant (HCL-v).

References

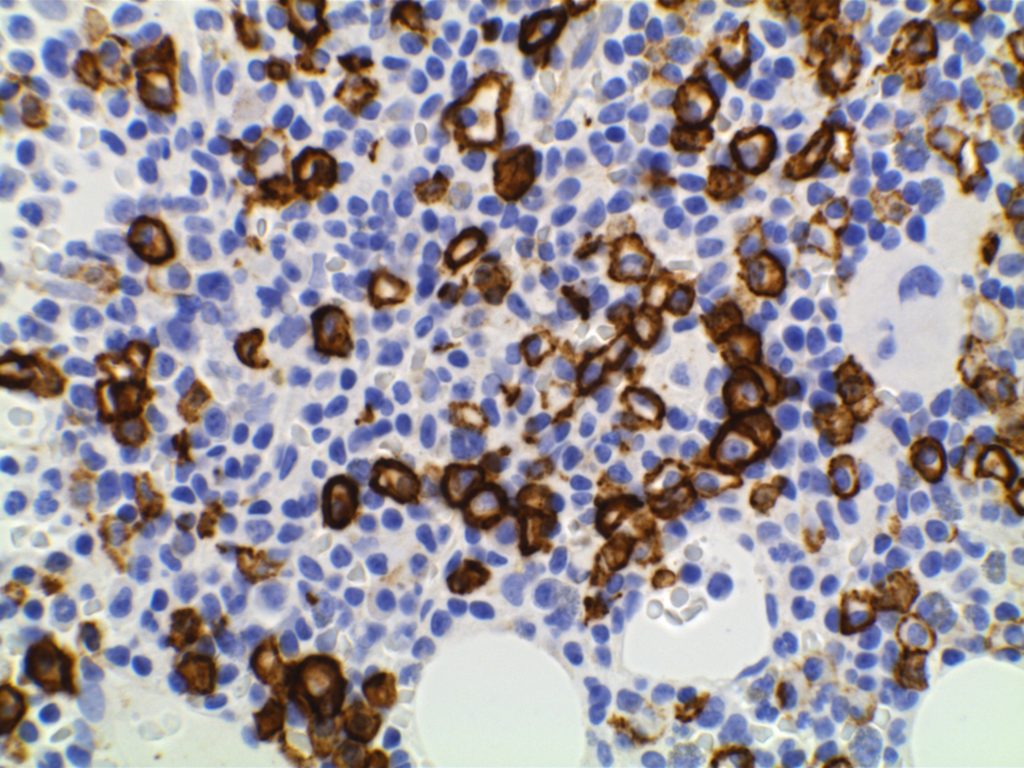

Mantle cell lymphoma

Morphology

2016 WHO Classification Revision

- IgHV unmutated/minimally mutated (mostly SOX11+) – classical disease that is aggressive, typically involves lymph nodes and other extra nodal sites.

- IgHV mutated (SOX11 negative) – associated with indolent non-nodal disease with peripheral blood and bone marrow involvement. Some of these cases may have been difficult to separate from CLL/SLL in the past.

Molecular Characteristics

- FISH + for t(11;14)

- Cytogenetics + t(11;14) ~70% of cases

- 50% of Cyclin D1 negative cases have CCND2 rearrangements

Immunophenotypic Expression Pattern

|

Marker

|

Comment

|

|

Negative

|

|

|

Positive (93-95%). Some data indicates up to 12% of MCL cases may be negative for CD5.

|

|

|

Negative. Up to 8% of cases may express CD10 (expression will usually be <30%).

|

|

|

Positive

|

|

|

Positive

|

|

|

Negative. 21% may express CD23.

|

|

|

Positive. Nuclear expression. The rabbit monoclonal antibody clone SP4 appears to have the highest sensitivity and stain intensity. Sensitivity ~95%.

|

|

|

Positive

|

|

|

Negative (~12% of cases may have expression)

|

|

|

Usually negative (35% may be positive, of these 2/3rds will also be bcl-6+)

|

|

|

Highlights the residual FDC meshwork.

|

|

|

Inverse relationship between quantitative Ki-67 index and prognosis. Ki-67 >40% is an adverse prognostic factor.

|

|

| Expressed in classic form and lack of expression is associated with more indolent variant of MCL. |

Important caveats

References

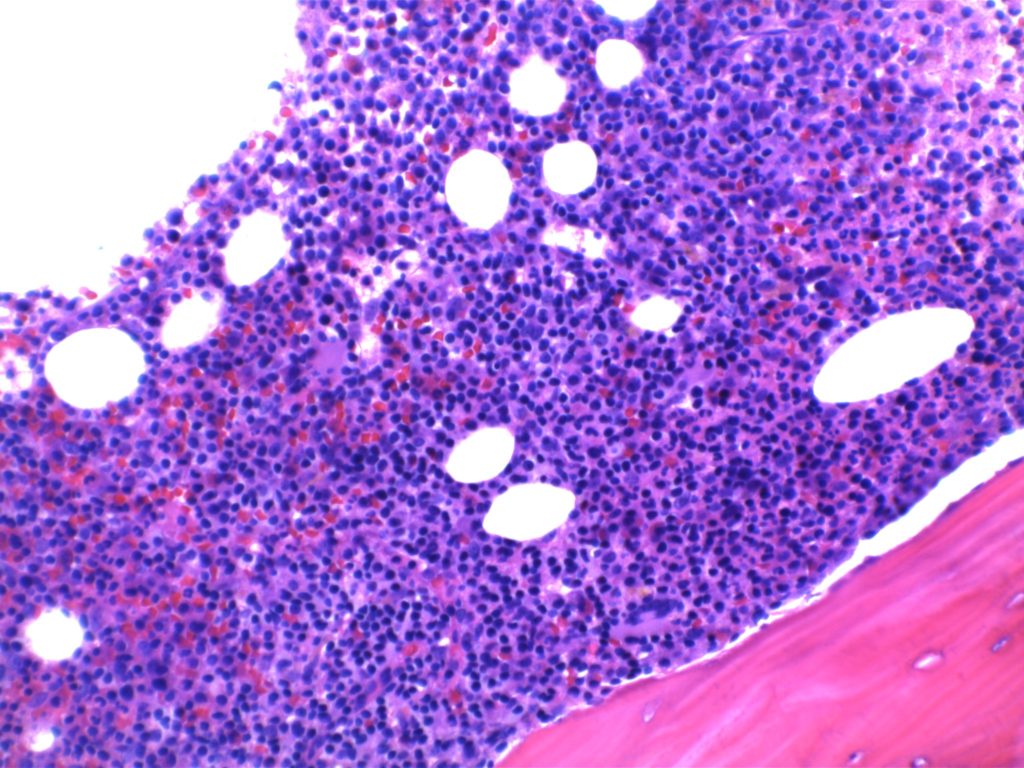

Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma (LPL)

Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma (LPL)

- Neoplastic proliferation of B-cells ranging in spectrum from lymphocytes to plasma cells (typically involves the bone marrow, but can also involve the spleen and lymph nodes).

- Bone marrow involvement

- Nodular, diffuse, and/or interstitial

- Small lymphocytes admixed with plasma cells and plasmacytoid lymphocytes

- IgM paraprotein

- Sometimes result in a hyperviscosity syndrome(30%)

- IgM and IgG paraprotein (minority)

- Some cases may be IgG or IgA.

- Cryoglobulinemia (20% of WM)

- Coagulopathy (IgM binds to clotting factors)

- MYD88 (L265P) point mutation (>90%)

- Results in up-regulation of NF-κB (promotes tumor cell survival).

- Not specific for LPL.

- LPL is a diagnosis of exclusion after other B cell lymphoid neoplasms with plasmacytic differentiation have been excluded.

- IgM MGUS is now thought to be more closely related to LPL than plasma cell myeloma.

Most patients present with non-specific B-symptoms. However, ~10% have hemolysis secondary to cold agglutinins (IgM binds to RBCs at temperature <37C).

Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia

- Cryoglobulinemia – precipitation of macroglobulins as temperatures <37C

- Bleeding – macroglobulins interfere with clotting factors

- Neurologic disturbances – secondary to increased blood viscosity

- Visual impairment – secondary to increased viscosity and hemorrhage

Immunophenotype

|

Marker

|

Comment

|

|

Negative

|

|

|

Negative (~10% +)

|

|

|

Negative

|

|

|

Positive

|

|

|

Negative (rare atypical cases +)

|

|

|

Positive (best marker). Marks from Mature B-Cells through Plasma Cell differentiation.

|

|

|

Often Positive

|

|

|

Positive

|

|

|

Negative

|

|

|

Positive

|

Morphology

References

MYD88 (L265P) Mutation

MYD88 mutation frequency

- LPL ~ 90%

- DLBCL ~ 30% (non-germinal center)

- DLBCL >50% (primary cutaneous, leg type)

- Multiple myeloma – negative (even IgM subtype)

- CLL/SLL – 2-3%

- Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma – 7%

- Splenic marginal zone lymphoma – 4-15%

- Nodal marginal zone lymphoma – rare

References

Breast – Atypical Lobular Hyperplasia (ALH)

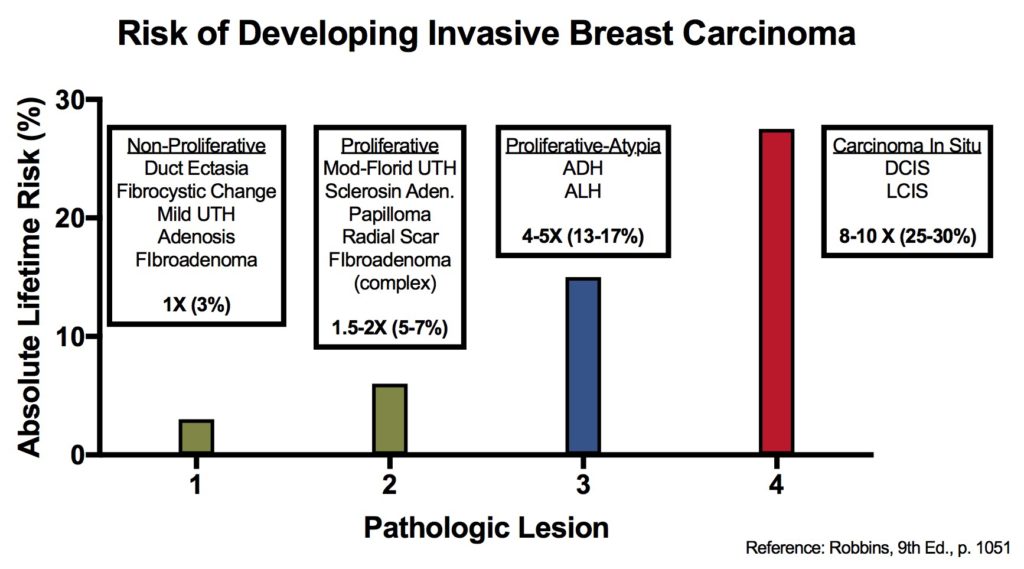

Breast lesions and risk of developing an invasive carcinoma

References

Kumar, Vinay, Abul K. Abbas, and Jon C. Aster. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. Ninth edition. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders, 2015. p. 1050-1051

Breast – Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia (ADH)

Breast lesions and risk of developing an invasive carcinoma

|

Relative

Risk

|

Absolute

Risk

(lifetime)

|

Breast

Lesion

|

|

1

|

3%

|

|

|

1.5 – 2

|

5-7%

|

|

|

4 – 5

|

13-17%

|

|

|

8 – 10

|

25-30%

|

References

Robbins, p. 1050-1051